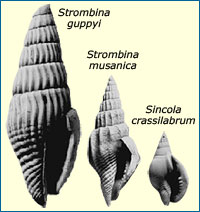

Paleontologists Ann Budd and Kenneth Johnson were interested in the factors that affect a species’ odds of surviving an extinction event — specifically, whether or not small body size increases a species’ chance of survival. To test this idea, they focused on a group of well-fossilized Caribbean snails (the genus Strombina) and studied many different species within this genus. Here’s the test they designed:

- Comparing outcomes. Using studies of the fossil record, Budd and Johnson gathered information about which of the snail species in this genus were present both before and after a mass extinction event, and which went extinct. They compared the shell size of species that survived the extinction to the shell sizes of species that went extinct during the event. If small body size upped species’ chances of survival, the “survivor” group should have had smaller body sizes than the “extinct” group.

- Controlling variables. The researchers wanted the only difference between the two samples to be whether or not the species in the sample had survived the extinction event. That meant limiting the study to a single genus of snails, so that species from one genus wouldn’t be over-represented in one of the samples; studying only adult snails, so that an excess of juveniles in one of the samples would not skew their results; and figuring out the actual shell size of snails with broken shells, so that this factor wouldn’t affect the size estimates for any sample.

- Avoiding bias. To minimize the role of subjective judgments in making the measurements, the data on snail sizes were obtained using a consistent method for measuring the shells. In addition, the researchers who collected the snail data sometimes ran into a problem: too many fossils. Some snail species were represented by so many specimens that it would have been too time consuming to measure all the adults. How did they decide which specimens to measure? If the specimens had been hand-picked for measurement, the person selecting the snails could have biased the sample toward larger or smaller snails. Instead, the researchers identified a random subset for measurement so that personal bias couldn’t skew the data.

The researchers obtained their measurements using a consistent method. Each snail specimen was measured from the tip of the spire to the base of the aperture. The researchers reasoned that this random subset would likely provide a representative sample of all the specimens of that species.

- Distinguishing chance from real differences. To make sure that any differences they found were not due to random flukes, the same measurements were repeated on many, many fossils — 5099, to be exact, from 72 different species within this genus. In addition, Budd and Johnson used a statistical test to determine whether the difference they found in extinction rates was likely due to chance or to a real difference in odds of extinction.

In the end, the test suggested that being small offers little or no protection from extinction: there was no significant difference in the sizes of snails that survived the mass extinction event and those that went extinct. Because Budd and Johnson designed their test so fairly, we can be confident in these results.

Photos of snails used in the study from the University of Iowa's Neogene Marine Biota of Tropical America (NMITA) database.